A basic diagram of an individual NEURON

The nervous system is a system of neurons, the nervous cells. A neuron consists of three parts: the body (soma), dendrites and axon. Dendrites and axon are filaments that extrude from the soma - typically multiple dendrites but always a single axon. The function of dendrites (and soma) is to receive signals from other neurons, while the function of the axon is to transmit signals further.

Where the axon of one neuron approaches a dendrite or soma of another neuron, a synapse is formed. This means that a synapse ( or a synaptic gap) is a structure that connects two neurons. Each neuron on average has about 15,000 connections with other neurons, so it is a very elaborate network.

The nature of information transmission in the nervous system is partly electrical and partly chemical. Every neuron has a certain threshold of excitation received from the other neurons. If the sum excitation exceeds this threshold the neuron "fires" - generates a brief pulse called action potential that travels along the axon to other neurons, passing the excitation further. The sum excitation is either on or off (1 or 0).

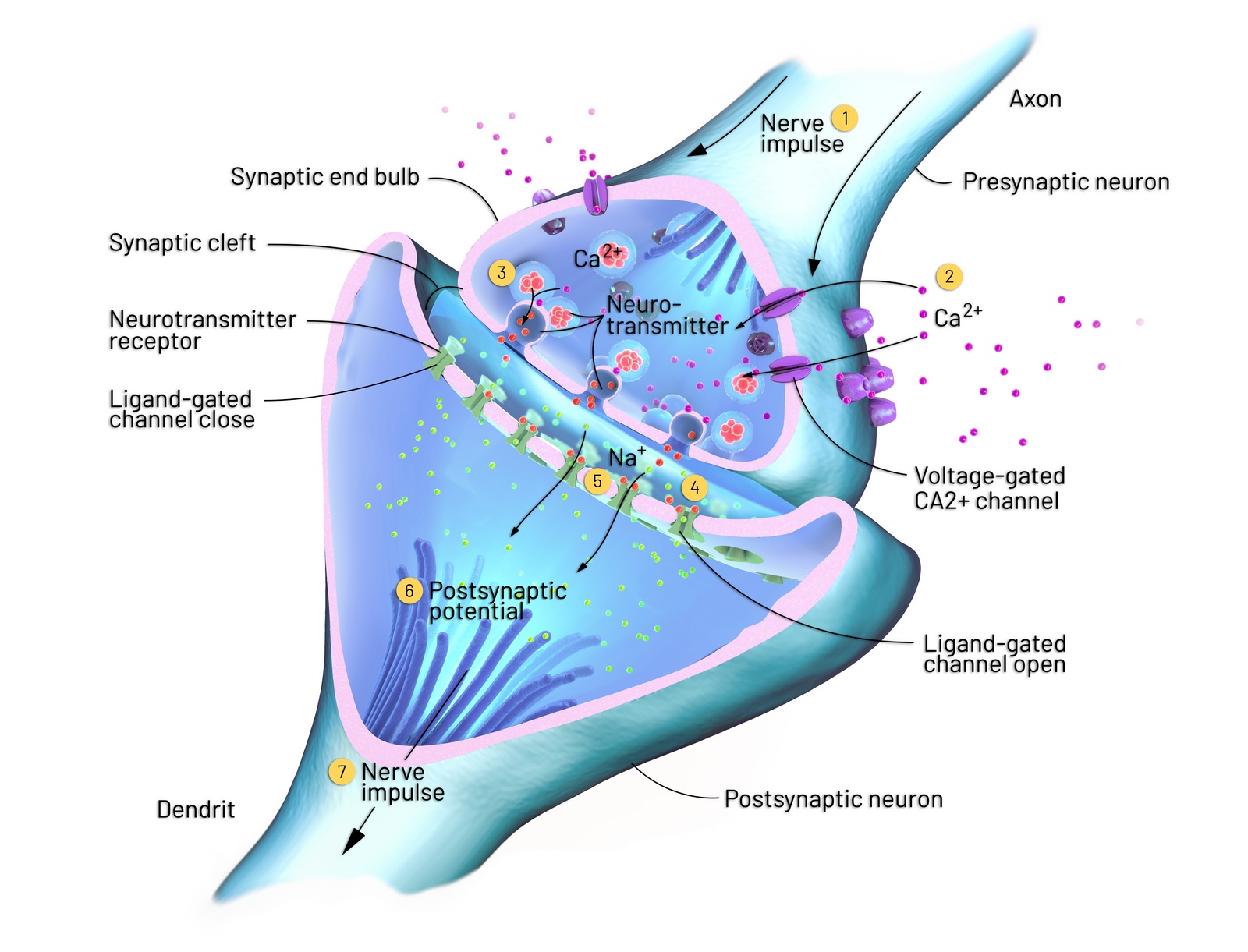

Axon terminal and synaptic gap

A basic diagram of the synapse and synaptic gap

Neurotransmitters firing and moving cross the synaptic gap

The pulse reaches the end of the

axon and there, at the synaptic gap, the mechanism of transmission becomes

chemical.

When the action potential reaches

the end of

the axon, a neurotransmitter is

released from the axon terminal into the synaptic gap.

Neurotransmitters are chemical

messengers. They are constantly synthesized in the neuron and moved to the axon

terminal to be stored there. A released neurotransmitter is available in the

synaptic gap for a short period during which it may be destroyed (metabolized),

pulled back into the pre-synaptic axon terminal (reuptake), or reach the post

synaptic membrane.

If the neurotransmitter binds to

a receptor in the post-synaptic membrane, this process changes the membrane

potential and so contributes to activating an electric pulse in the

post-synaptic neuron. Here the chemical mechanism becomes electrical again.

There are many different

neurotransmitters. Their exact number is unknown but more than 100 have been

identified. All neurotransmitters are broadly divided into two groups:

excitatory and inhibitory.

Inhibitory neurotransmitters stop

the impulse, preventing it from crossing the synapse. They produce calming

effects on the brain. These neurotransmitters are always in a state of dynamic

balance. When excitatory or inhibitory neurotransmitters are out of their

optimal ranges in the brain, this may cause various behavioural

malfunctions such as mental disorders.

Neurotransmitters themselves are

affected by agonists and antagonists. Agonists are chemicals that enhance the

action of a neurotransmitter. Antagonists are chemicals that counteract a

neurotransmitter and so prevent a signal from being passed further.

Many drugs function as agonists

or antagonists. For example, a class of drugs known as SSRIs (selective

serotonin reuptake inhibitors) selectively inhibit (block) the reuptake of the

neurotransmitter serotonin from the synaptic gap. This increases the concentration

of serotonin in the synapse. SSRis

have been shown to be effective against depression.

We must always be cautious about reductionism. Human behaviour is rarely, if ever, that simple.

Imagine we have artificially

increased the level of neurotransmitter X in the brain

and this resulted in a change of behaviour

Z (for example, elevated mood). Can we say

that neurotransmitter X

influences elevated mood?

Yes, to a certain extent, but

with a lot of limitations to be kept in mind.

X

may function as an agonist for neurotransmitter Y, which in tum may affect behaviour

Z. In other words, the effects of neurotransmitters may be indirect, sometimes

with many links between the "cause" and the "effect".

X

may serve as a trigger for a long-lasting process of change in a system of

interconnected variables. In other words, the effects of X on Z may be

postponed.

X

is usually not the only factor affecting Z. X

is never the only factor that changes. As you artificially increase the level

of X, this may result in various side effects.

Research into the influence of

neurotransmission on behaviour

will therefore always be reductionist in the sense that we need to manipulate

one variable (X) and assume that it is the only variable that changes.